The Rose Haven House

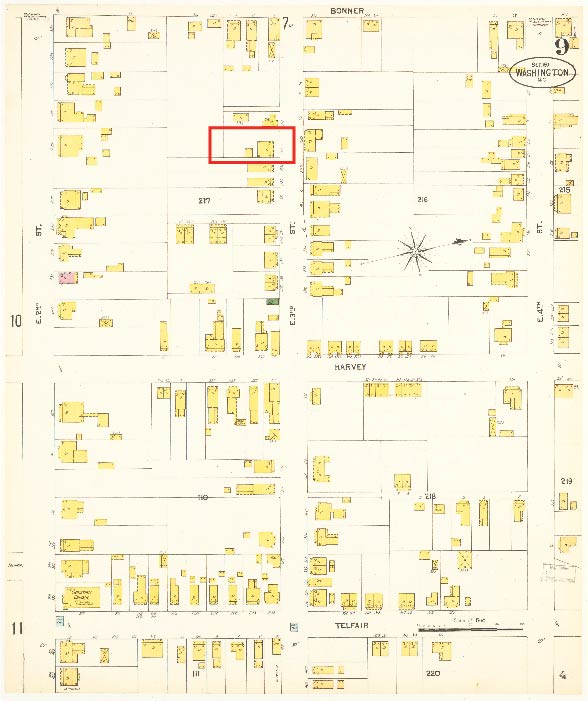

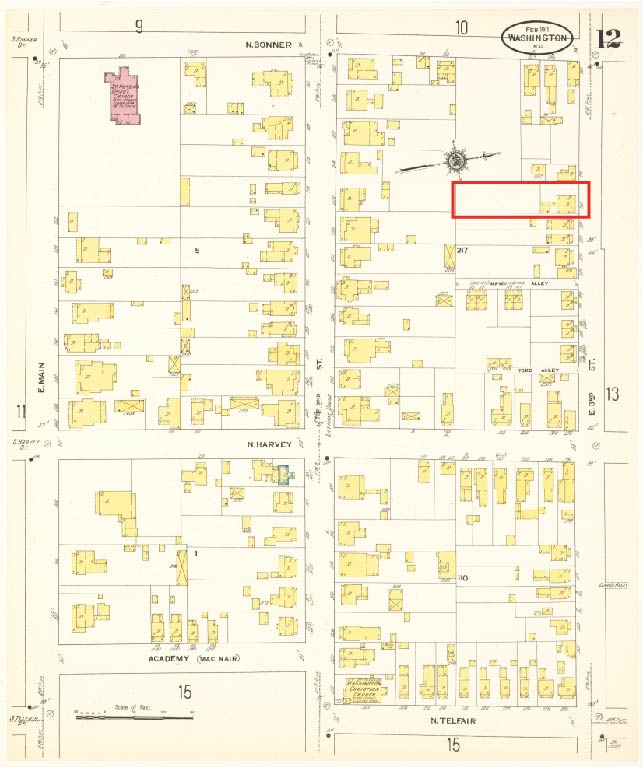

One of three cornerstones of the Rose Haven Center of Healing is the soon to fully renovated 1892 farmhouse at 219 E. 3rd Street, Washington, NC.

The Rose Haven House is a four bedroom, 1400 sq foot house. It is simple and functional in design and for 130 years, it served as affordable housing for underrepresented and working-class residents of Washington. The Center is located in the historic district and the Rose Haven House is one of the older residences in Washington.

Soon, the Rose Haven House will support a variety of programming consistent with our mission to advance wellness and resilience to women Veterans:

- Restarting one day and multiday wellness retreats

- Group sessions

- Book clubs

- Nutrition/cooking classes n

- And more…

In 2017, Pamlico Rose Institute purchased the future Rose Haven House for $17,000, one small step away from demolition. Included in that purchase was the adjacent barn. You can follow the renovation’s progress over time through our video series, Renovating Haven located on our YouTube Channel.Rose

The house had been uninhabited for over a decade, every now and then serving as a roof over the heads of local homeless. You can learn more about the history of the Haven House here and the deed search done by the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office here.

As selection of moldy and mildewy carpet was in every room and walls were peeling wallpaper or exposed drywall; a room or two featured old tongue and groove or shiplap on walls and ceilings. Ceilings were low, especially upstairs where the headroom was barely 7 feet. With a steeply pitched roof, the attic was almost a windowless 3rd story. There were twenty-three windows in various stages of distress with rotting wood frames. A rusted tin roof was held up by suspect exterior clapboards and vines grew out of pane less windows.

In a number of “demo day” workdays in late 2017 and early 2018, the Haven House’s interior was taken down to the studs. Gutting the house revealed a typical balloon structural design with termite damaged beams and tresses and in the original part of the house, bark still on both.

The renovation needed to hew to the historic commission guidelines on the exterior house, “replacing like with like” including using wood siding and refurbishing or buying wood windows and the tin main roof.

The plan for the interior was to incorporate as much as possible design elements that would make the house safer and less threatening to women Veterans who may be struggling with the effects of trauma, to include

- the use of soft non-threatening colors and hues throughout the house

- getting rid of the second-floor claustrophobic feeling by opening up the rooms through building a vaulted ceiling

- retaining the large number of windows providing an abundance of ambient light through the day and into the evening

- opening up the downstairs’ living space

Renovating with preservation as a metaphor aligned with our approach to healing through wellness and resilience, one heals from within, often there is a dramatic self-change even though little may have changed physically, except perhaps in better physical health. You can learn more about that connection here. Every attempt was made to salvage and recycle as much as possible wood and other components from the original house into the renovation. Taking something old and making new, or upcycling was incorporated in the design, and also was the driving motivation behind our woodworking program GRIT Restoration. Much of the furniture is made or being made out of reclaimed pieces of the original house learn more about GRIT Restoration here.

The benefits of historic preservation of residences and businesses alike to the owner, neighborhood and the community are many, including economic development, environmental preservation, community beautification and neighborhood safety.

Old can be good

Published by Washington Daily News, November 17, 2017

By Robert Greene Sands

The pink flap of covering on the wall upstairs in our old house at 219 E. Third St. only partially hid a deeper layer, barely visible. I reached over and gently grabbed one end and started to separate it from the wall. It was thin, just an aged layer of dried paint. As the layer came away from the wall, I was greeted not with other layers of paint on the plaster, or even wallpaper, but a newsprint page dated May 31, 1957, from the Washington Daily News. The more I gently pulled, the pages of the newspaper were exposed, stretching out from all sides of the tear. I was exposing a workingman’s wallpaper.

In the same room, now gutted, the skeleton of studs revealed wood with the original tree bark still attached.

Upstairs bedroom revealing beams with bark still attached.

Downstairs, with the ceiling exposed, beams reflected a journey of necessity, walls advancing and retreating over the decades as families adjusted the physical structure to fit their needs.

More than 120 years or more of diverse owners and a score of boarders and renters, the beams and studs, the walls and floors, tell a story of a blue-collar dwelling, still standing because of its adaptability to need. Photos over the last 80 years and maps dating back to the turn of the 20th century capture an evolution of structure and purpose, first an outbuilding, then an attached one, a barn, a fire, and yet a new barn. The house stood near the curb, then was moved back and raised.

People lived in the house as it stretched and breathed to meet the needs of its inhabitants. Agile and flexible, in all its permutations and gyrations the house became a home for each of the families and boarders across the decades for diverse Washingtonians living under its ageless, rolled-seamed roof.

Confronting crisis or longstanding issues means solving problems. In some cases, attacking the problem involves rendering physical or social structures into rubble before starting over. If a link in a chain, or even a whole section of fence is rusted and hanging by a thread, replacement may be the only solution to retain the structure’s integrity. New could mean increased “strength” or resilience. But what if new or starting over actually means reduced resilience?

Historic preservation and historic districts are good examples of this principle, where community resilience is promoted by preserving the integrity of the individual structure, like our old house, to bolster the authenticity of the larger district. A mouthful, I know, so let’s dig deeper.

A historic district, like Washington’s, reflects a residence pattern 120 years ago that promoted a tightly-knit community, where businesses, recreation and the river were within walking distance. Often residences were located above businesses. Many urban places, reproducing this historic pattern, have brought economic and cultural growth to cities like Washington, including the ever-present Main Street and surrounding neighborhoods. Maintaining that sense of historical continuity reinforces a sense of neighborhood identity and, in turn, promotes community resilience.

Rehabilitating structures within the historic district — while also setting up programs to intercede with owners prior to houses falling into disrepair — preserves the district’s integrity and fills in “gaps” of empty space or failing structures that disrupt historic continuity. Rehabilitation also reduces security issues linked to vacant and rundown buildings.

Many historic houses have stood for years because owners built them to last generations. Bringing back to life and giving new purpose to old houses takes advantage of the solid “bones” of many historic houses. Our house was built to last as a home for an extended family. The fact that three, even four generations called the house home at the same time is apparent in the flexibility we see in the modifications to the house.

Building community resilience demands adaptability to different situation, and the ability to sustain solutions to problems with long-term success. Problem-solving is better met considering an array of options and not just “tossing out the baby with the bathwater.”

Our old house in its solid bones gives us a good foundation for our [Center] for female veterans, but also provides a lesson on building community resilience by paying attention to the past.

Robert Greene Sands is an anthropologist and CEO of the nonprofit Pamlico Rose Institute for Sustainable Communities located in Washington.